After long preparations in Lebanon, the PKK Guerilla took up arms against the Turkish state exactly 40 years ago – on 15 August 1984. The 29th Kurdish uprising in the history of the Turkish state continues to this very day and has long since spread to all four parts of Kurdistan. The revolution in Rojava, the victory over the so-called Islamic State and the Democratic Autonomous Administration, which now controls almost a third of Syria, are the fruits of this 29th uprising. Even though the armed struggle began in Bakur (Northern Kurdistan / ‘Southern Turkey’) and focussed on this part of Kurdistan for a long time, it also had a profound influence on the population of Rojava (Western Kurdistan / ‘Northern Syria’).

A (very) brief history

After Kurdistan was divided between the nation states of Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria in 1923 under the Treaty of Lausanne, the Kurdish population in all four parts was subjected to severe assimilation. From then on, the existence of the Kurdish identity was denied. Kemal Atatürk probably summarised this practice with his famous phrase ‘One country (Turkey), one flag (the Turkish flag), one nation (the Turks), one language (Turkish), one state (the Turkish state)’. According to this logic, there was no room for the Kurdish people and all the other nations on the territory of the newly born Turkish state. The Syrian rulers also declared ‘Arabness’ to be the unifying element of all people living in Syria. When Hafez al-Assad came to power in 1970 his ideology of pan-Arabism propagated by the Ba’ath party, increased the pressure on the Kurdish population once again. Examples of anti-Kurdish measures at this time include the establishment of an ‘Arab belt’ in Rojava, meaning the artificial settlement of Arabs in the Kurdish regions in order to prevent the Kurdish identity from being lived out properly. The practice of denying citizenship to the entire Kurdish population and only granting them ‘refugee status’ on their own land has also been applied. In this way, all opportunities for advancement and co-determination for Kurds were destroyed right from the beginning.

Without the resistance led by the PKK, there would probably be no Kurdish consciousness today, neither in Bakûr nor in Rojava. The co-chairman of the Executive Committee of the KCK (Koma Civakên Kurdistan) and founding member of the PKK, Cemil Bayik, describes the historical context of the offensive accordingly as follows: ‘This shot had to be fired because the Kurdish people were threatened with extinction. Nobody really knew whether the Kurds actually still existed. The people were in a kind of deathly sleep and this situation had to be brought to an end.’. Here alone you can see how essential the beginning of the guerrilla struggle was for Kurdistan in general and Rojava in particular, because without it there would have been no Kurdish people with highly experienced guerrilla units in 2012 that could take on the role of pioneers and trailblazers of the Rojava revolution.

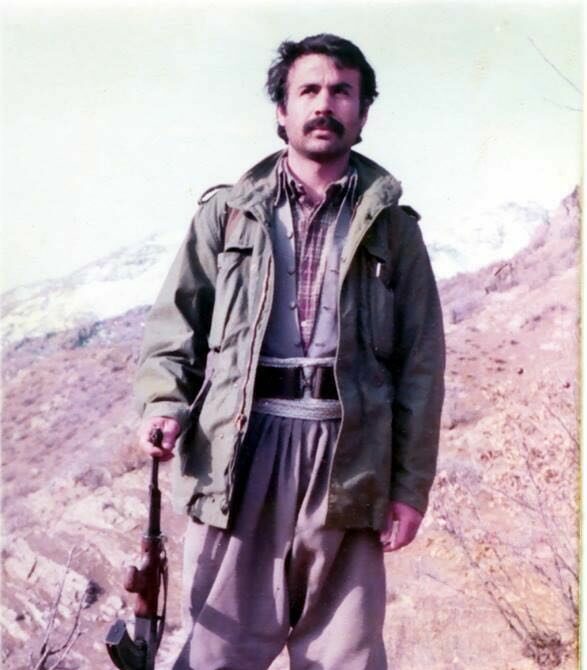

The 15 August offensive

The 15 August offensive itself consisted of two attacks on the cities of Dih (tr. Eruh) – under the leadership of commander Egîd – and Şemzînan (tr. Şemdinli) under the command of Gözlüklü Ali. The focus of these actions was not so much to archive a purely military, but more an propagandistic victory. The fighters were also referred to as ‘armed propaganda units’, a concept that was used by numerous other revolutionary groups aswell such as the IRA in Ireland, the Tupamaros in Uruguay or the RAF in Germany. In Commander Egîd’s group of just 29 fighters, six of them alone were assigned to pure propaganda work, sticking up posters and reading out leaflets over the mosque’s loudspeakers. The fighters remained in the city from the beginning of the attack – at around 9 p.m. – until midnight and were able to retreat without losses and with numerous captured weapons. On that day, the fighters proved that the Kurdish people had not yet been defeated and that the Turkish colonisers were vulnerable. Frantz Fanon wrote the following in his book ‘The wretched of the Earth’: ‘When the colonised kills a colonialist, he kills two people: the oppressor and the oppressed, whom he has oppressed in himself. (…) what remains is a dead man and a free man.’ On this day, the armed propaganda units were primarily killing the Kurdish people’s fear of their colonisers.

Impact on Rojava

The revolutionary movement was already active in Rojava long before 15 August. But the offensive paved the way for a great leap in the quality and quantity of work. The spirit of the offensive inspired large sections of the population. The PKK quickly became the strongest political force in the region and began to reorganise social life with considerable success. The book ‘Licht am Horizont (Light on the Horizon)’, published in 1999, 13 years before the revolution, already states the following: ‘In percentage terms, the party has the strongest base in the “Little South”, in Syrian Kurdistan’. Without these years of social work and organisation, driven by the events of 15th of August, a revolution would have been unthinkable. Initially, the focus of the work in Rojava was still on supporting the guerrilla struggle in Bakur and Başûr (southern Turkey / northern Iraq), because due to the small number of Kurds in Rojava, it was assumed that the revolution would break out there last. Ayşe Efendi, former co-chair of the PYD in Kobanê, commented on this topic in an interview published in the book ‘Rojava: Peoples in Arms’ as follows: ‘At that time, we were thinking that Bakur , where there are 20 million Kurds, would have a large uprising which we would join. We were supporting each other, but we were expecting what happened in Rojava to happen in Bakur, because there are only 4 million Kurds here. Of course, we were not anticipating the Arab Spring, where so many people would rise up.’ In their efforts to support the armed struggle, the people of Rojava collected food, money and materials, among other things. You can read a wonderful example of this in ‘Licht am Horizont’: ‘Once a year there is the lentil harvest. The party has leased larger fields. At harvest time, a day is set when the people are called together. Then everyone, whether doctor, taxi driver or housewife, goes to the fields together to bring in the lentil harvest. Other work for the party is organised in a similar way.’

Numerous teenagers and young adults from Rojava have also joined the guerrilla struggle in the mountains. Many of them, such as Şehîd Xebat Dêrik, one of the most important key figures in the founding of the YPG, or Heval Mazlum, general commander of the SDF, came back from the mountains to Rojava at the beginning of the revolution to support the uprising. The defence of Kobanê, the fight against Daesh, none of this would have been possible without the many PKK cadres joining the fight, many of them originally from Rojava.

In short, 15 August laid the ground on which the Rojava Revolution would blossom 28 years later. Without the leap in the organisation, ideological depth and military professionalisation of the Rojava population triggered by the offensive, it is likely that the Syrian state or the Islamic State would now be in control of northern and eastern Syria rather than the self-administration.

72 hours turned into 40 years

Immediately after the successful offensive, the general of the 1980 military coup and then President of Turkey, Kenan Evren, announced that the ‘looters’ and ‘terrorists’ behind the attacks would be found and eliminated within 72 hours. Today, 40 years later, the Turkish state has still not succeeded in liquidating the guerrillas. The reality of Kurdistan has been fundamentally changed in almost every aspect in these 40 years. Only one thing is still exactly the same as it was 40 years ago. The current Turkish president is still announcing that the destruction of the Kurdish resistance will be realised in the near future. The resistance of the last 40 years paints a different picture. The revolutionary forces are still fighting and developing. The spirit of 15 August still pulsates in each and every one of them, in all the revolutionaries on the ground.